Forty years after riots broke out in Toxteth, changes sparked by the unrest have led to a “complete transformation” of Liverpool.

During nine days of civil unrest in July 1981, 468 police officers were injured, 500 people were arrested and 70 buildings were damaged so severely by fire they had to be demolished.

The riots, which saw the worst of the violence on July 5 and 6, were sparked by the arrest of a young black man.

In the four decades since, the city has seen huge regeneration, was named the European Capital of Culture in 2008, has a visitor economy worth £4.9 billion annually and this year elected its first black mayor.

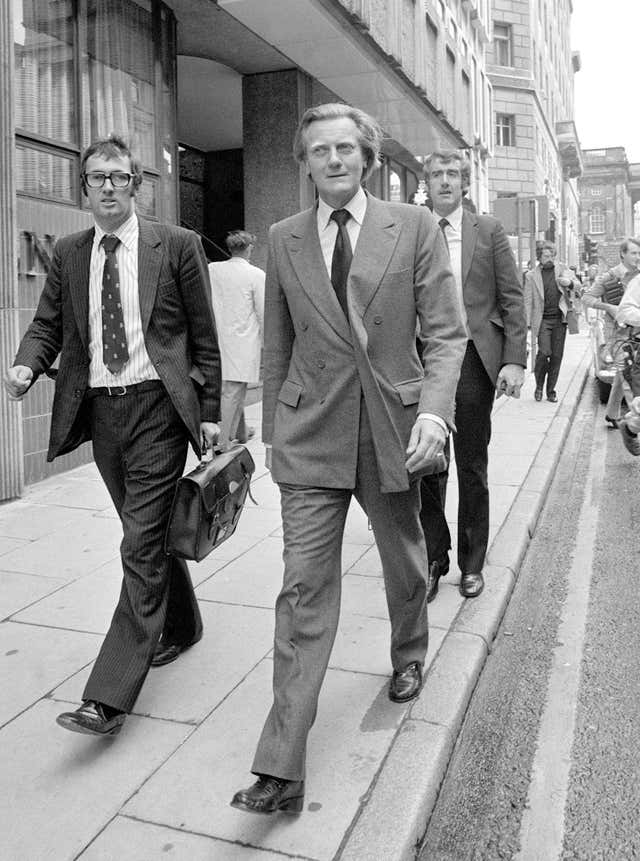

For Lord Michael Heseltine, who had taken up the post of minister for environment two years earlier, there was a sense of “personal responsibility” as he saw the riots unfold.

The Conservative peer, who was given the Freedom of Liverpool in 2012, had already been working on plans for the city’s regeneration.

He told the PA news agency: “I’d been involved for two years and I had not realised the intensity of this problem.”

Lord Heseltine said the rioting “injected a degree of urgency” into the plans.

For others though, the shocking scenes had been predictable.

Dave Clay, 70, was working for the Merseyside Community Relations Council at the time and a member of the Liverpool Black Organisation, who he said warned a parliamentary committee of trouble to come in 1980.

Mr Clay, author of A Liverpool Black History, cited problems with employment, housing, education and the police relationship with the black community.

He said: “My feelings at the time were anti-police.

“I was in no doubt whatsoever, in most of my experience of life the police were being racist.”

He said while he had been focused on organising the community to tackle the problems, a younger generation responded differently.

“We can say that they should have or shouldn’t have but they did,” he said.

“The police escalated things and it blew into a major, major confrontation.”

In the aftermath of the riots, Lord Heseltine spent three weeks in Liverpool and for the next 18 months worked on projects for the area.

Speaking to people at the time, he said, there was no “positive movement” or “leadership”.

But, he said when he returned to the city in 2011, the difference was “absolutely staggering”.

He said: “Everybody we saw had ideas and said if you help us, you give us the opportunity, we will be able to make things happen.

“It was a complete transformation.”

Even now, after the city’s key hospitality and tourism industries have been hit by the coronavirus pandemic, Lord Heseltine said he does not believe Liverpool will ever go back to where it was in the early 1980s.

He said: “I think the progress is built into the system so much, there is so much enterprise in the public and private sectors.”

Mr Clay, who was part of the L8 Defence Committee formed to provide support to residents during the riots, agrees the unrest brought about change, but not necessarily the change the community wanted.

He said: “They took the soul away from the community.”

He said as people were moved out of the area and many of the buildings demolished the community was broken up.

Improvements to the area were designed to attract the middle classes and the investments in the city did not empower black businesses, he said.

But, Mr Clay acknowledged Liverpool now has its first black MP, Kim Johnson, saw its first black Lord Mayor when Anna Rothery took up the role in 2019 and this year elected its first black city mayor, Joanne Anderson.

He said: “I know there are lots of young black people who are opening doors.

“It’s not all negative.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here